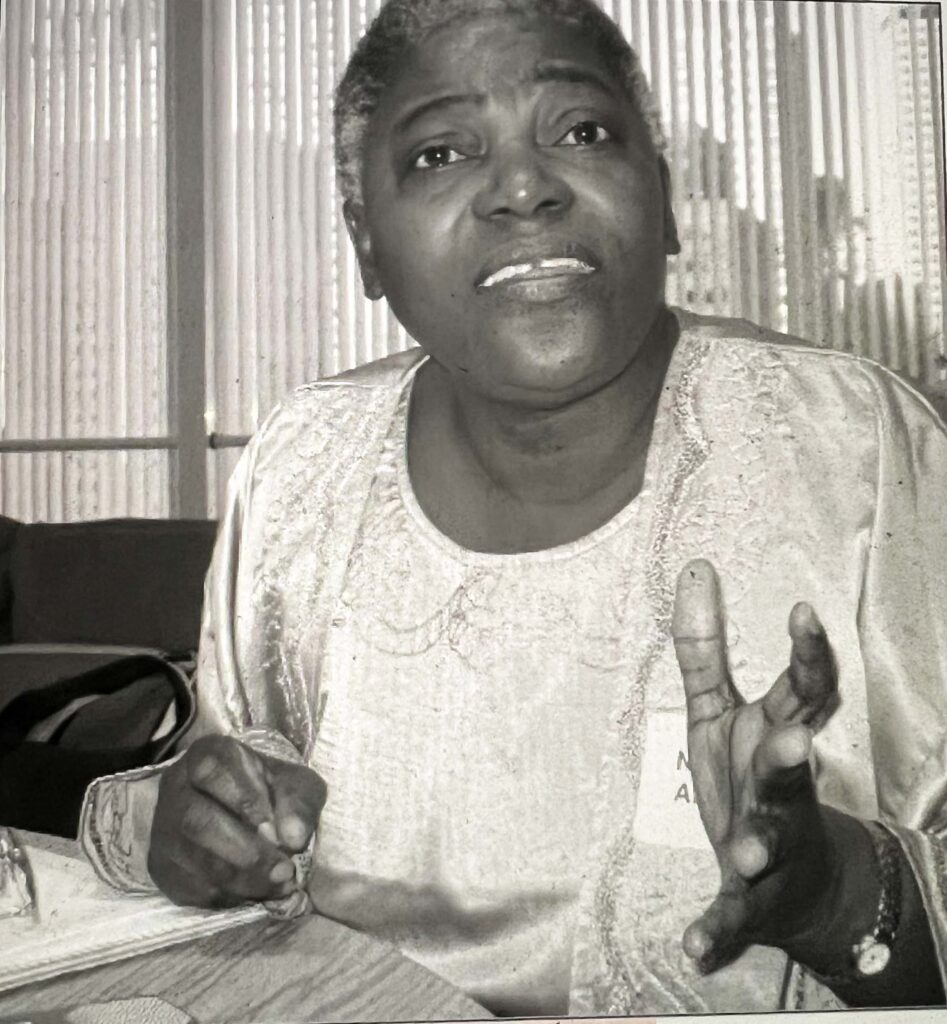

In March 2004, we published an interview with Septuagenarian David Olupitan on the genesis of mistrust between recent African immigrants and African Americans as well as Blacks born outside the shores...

You are not authorized to read this page without a username and password. It is time to register and subscribe to have unlimited access to everything The Chicago Inquirer has to offer. You can do a monthly, quarterly, six months or yearly subscription.

SUBSCRIBE NOW!!!

and enjoys unlimited access to news, analysis, archives, sports, culture, interviews, and many more.

Not a member? Subscribe or login below: